In 1949, James Thurber was nearly completely blind, and behind schedule on a book. He headed to Bermuda, in hopes that the change of scenery would encourage him to get some work done. Instead, by his own account, he found himself thinking of an evil Duke, a lovely princess, and thirteen clocks. Calling it “an example of escapism and self-indulgence,” Thurber grew obsessed with the book, tinkering and tinkering and tinkering again, until—again in his own words:

In the end they took the book away from me, on the ground that it was finished and that I was just having fun tinkering with clocks and running up and down secret stairs. They had me there.

The result, The 13 Clocks, would be one of his most striking works: something between a fairy tale and a fable, a story and a poem, but always, always, magical.

The process of writing the book was immensely challenging for Thurber. Still accustomed to writing by hand, he would scribble down his words in pencil, then wait for assistant Fritzi Kuegelgen to transcribe his words and read them back to him, painfully accepting correction after correction. By Thurber’s account, he and Kuegelgen went through the manuscript at least a dozen times, ironing out errors. It seems possible that Kuegelgen may have been instrumental in taking the book away from him, although that is not specified.

Thurber’s near blindness also made it impossible for him to illustrate the book with the cartoons he had created for previous works and The New Yorker. Thurber approached illustrator and cartoonist Marc Simont, at the time perhaps best known for letting his roommate, Robert McCloskey, keep ducklings in their bathtub. The adorable birds, if not the bathtub, ended up immortalized in Make Way for Ducklings, which won the Caldecott Medal in 1942. Simont, meanwhile, worked in advertising before joining the U.S. Army in 1943-1945. When he returned, he began his storied book career, primarily for Harper Collins, but occasionally for other publishers—including, as with The 13 Clocks, Simon & Schuster.

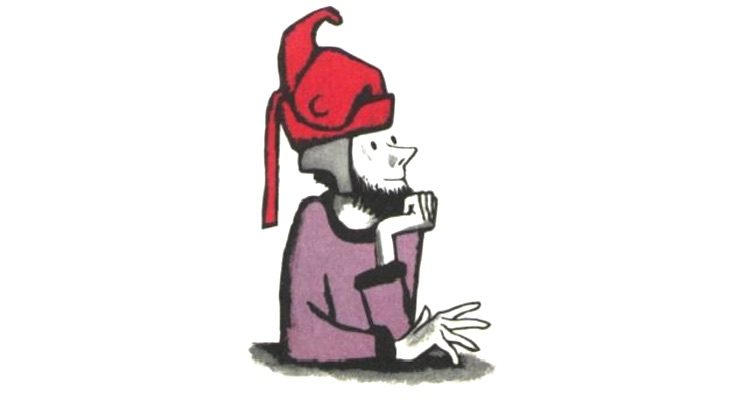

By 1949, Simont had several projects on hand, including Ruth Krauss’ The Happy Day, which would win him his first Caldecott Honor. But he happily agreed to work with Thurber, and in particular, to create the indescribable hat worn by the Golux. Legend claims that Thurber was satisfied when Simont was unable to describe the illustration he had created (it’s kinda but not exactly like a fat twisted pink snake, or a candy decoration gone horribly wrong, though that’s not quite the right description either).

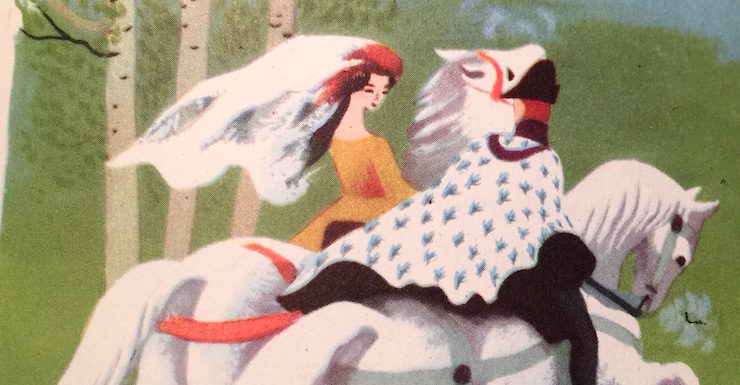

And what was this tale that obsessed Thurber so much? Well, it’s partly about an evil Duke, and his beautiful niece (who, SPOILER, is not EXACTLY his niece) Princess Saralinda, and the thirteen clocks in their castle, which have all frozen at exactly ten minutes to five. This pleases the Duke, who is always cold, and afraid of Now, with its warmth and urgency. And it’s also about a minstrel, Xingu, whose name, I was surprised to read, is an actual plot point, showing the care Thurber took with this book, and who is also a prince in search of a princess. And it’s about Hagga, who once wept jewels, and now no longer weeps. (A sidenote in this part of the story suggests that Thurber had read the fairy tale of Diamonds and Toads, and shared my strong doubts about the story’s economic impact.) And it’s about the magical Golux, who wears an indescribable hat, who often forgets things, and whose magic cannot be relied upon.

It is difficult not to see the Duke, who injured his eye during childhood, as some sort of stand in for James Thurber, who also injured his eye during childhood. As Thurber was with the book he was supposed to be writing, but wasn’t, the Duke is trapped in stasis; other people move around him, but he does not. Presumably unlike Thurber—but perhaps not—the Duke clings to this stasis, creating conditions that make it difficult to impossible for anything in the castle to change, without a touch of magic, that is. That entrapment, in turn, has helped sharpen the Duke’s cruelty.

Buy the Book

The 13 Clocks: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

I do not want to suggest that Thurber, like the Duke, actively tried to kill or destroy anything that could or would change that entrapment—although, come to think of it, the focus on this book did leave the work on the other book at a standstill, so, maybe. But rather, The 13 Clocks is more about what can happen to people terrified of change, and of the lengths those people can and will go to in order to prevent that change.

If possible, I recommend either trying to read the book out loud, or listening to one of the recordings made of the text—including, the internet claims, one by Lauren Bacall that I was not able to track down. Partly because Thurber intended the story to be read out loud—it is, at least on the surface, a children’s tale, though I would argue it is equally meant for adults—but mostly because reading the work aloud or hearing it allows the works careful, precise meter to shine through—showing what this work also is: a prose poem, if one with dialogue and paragraphs, and moments of rhyme, like this:

For there’s a thing that you must know, concerning jewels of laughter. They always turn again to tears a fortnight after.

Even if you can’t read it out loud, or hear it out loud, The 13 Clocks is well worth the short read, especially if you need a touch of magic in your life.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.